Joy illimited... just how hopeful is 'The Darkling Trush'?

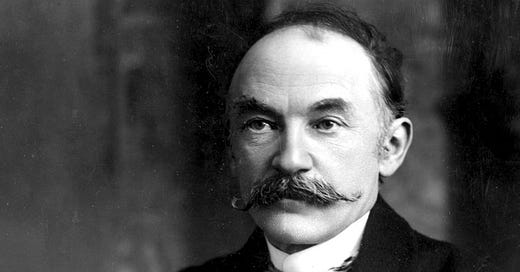

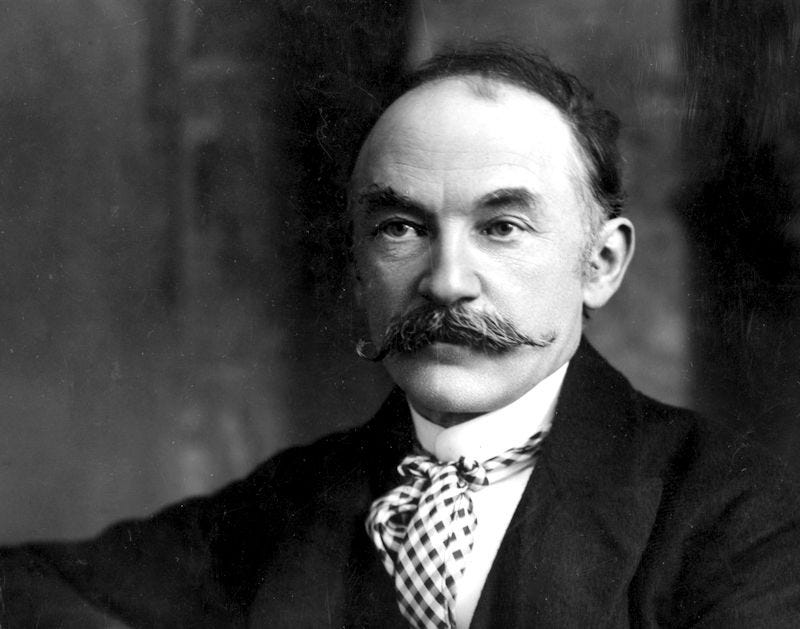

Thomas Hardy's (un)happy new year

The Darkling Thrush is one of the most anthologised poems in the English language and for good reason. Though it was written for the end of a century, the weary but undimmed hope held by Hardy’s thrush still seems to capture something fundamental about how we feel about the turning of the year.

Just how hopeful is Hardy’s thrush? This is a poem in which the landscape is compared to a sepulchre. It is the deadest part of winter. Even the ‘aged’ thrush is ‘frail, gaunt, and small’. Still, he sings, flinging his ‘soul / against the growing gloom’ and in that act of defiance Hardy wonders whether there isn’t a sign of something better to come:

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

Carol Rumens suggests that this is Hardy, the famous pessimist and author of some of the most depressing novels ever written (this is not a criticism), at his most optimistic. For John Berryman, those final lines should be read ironically: the ‘blessed Hope’ is a fiction.

The English poet-critic Donald Davie, meanwhile, argued that ‘The Darkling Thrush’ wasn’t only ironic, but downright cynical. Knowing that ‘up-beat, unexceptionable’ poems were the ones most likely to be celebrated and anthologised (they are also the ones which go viral on social media), Hardy went out of his way to write one himself. By 1900, Hardy was a literary celebrity, and the final stanza as a self-deprecating reference to his own reputation: he is ‘unaware’ of the hope to come, because he is such a notorious grump, but the bird knows better. Spring, obviously, is on the way.

Who, after all, is the darkling thrush? Davie doesn’t go this far, but Hardy’s description of the bird is remarkably, suspiciously, precise:

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom

Hardy was sixty in 1900. We don’t tend to think of birds as ‘gaunt’, but humans often get that way. In fact, we’ve no reason to think the poet has even seen this bird; the voice simply rises among the twigs. If he had seen it, how would he have known it wasn’t just ill? Hardy was a small man who took care over his appearance. ‘Blast-beruffled plume’ sounds about right.

But Davie was being a bit too clever himself. Winter always ends (in the future it may never get started, but that’s another question), but it doesn’t always feel that way. Despite the bleak winter fields, despite his own bleak self, Hardy finds himself composing a poem, flinging his soul upon the growing gloom. The last stanza might be ironic, but it's true (irony is part of the world). Hardy doesn’t know why he’s singing. He can see no justification for it. He does it all the same.1

In what I can only assume was the doing of a Christmas poltergeist, Substack recently ‘featured’ this newsletter, which has resulted in a lot of new subscriptions. I’m not just being English and self-effacing when I say that this must have been a mistake. I don’t post often and have never had more than a handful of readers (most of whom are friends and family). It’s a personal blog with a niche remit: I mostly write about poetry, and most of the poetry I write about is English and/or British poetry from the 20th century. In short, you’re very welcome, but it’s strange to think you might be there - strange in the way that all writing online is uncanny. You sit in your chilly little flat in south London, write a blog, and anyone, anywhere, can read it.

I’ve been thinking about ghosts a lot recently, especially ghosts as a way of thinking about writing. Back in the tail end of 2023, I wrote something for The London Magazine about the ways in which poets haunt second-hand bookshops. I also wrote something for Engelsberg Ideas about Charles Dickens and the ghosts haunting his story ‘The Signal-Man’. If you’re new here, this piece and those links are a good indication of the kind of thing you’ll find. If you still want to stick around, please do. If you’ve had your fill - Happy New Year, and catch you later. Wherever you are.

I’ve edited this piece to better reflect what I think Donald Davie was arguing in Thomas Hardy and English Poetry (the original version implied Davie wasn’t thinking about the seasons when he described the poem as ironic, but I suspect he just takes it as read). It doesn’t change my central point: the poem is both cynical and sweet.

I really liked this Jeremy, thanks. Probably like a lot of people, I've known the poem for so long that I've never really worried much about what it meant or why he wrote it, but I agree with you that Davie's reading, though bracing & very stimulating, is probably over clever. Or rather, I can believe that he might be right about Hardy's conscious intentions, but if so, the poem escaped his cynicism -- accidentally sincere, perhaps. It always makes me remember my grandmother, who was born on Christmas Day 1900.

I am not a fan of Hardy for precisely the darkness, got enough of it in the real world already! I liked your post, especially the bit about unwanted subscribers.