Around this time of the year magazines ask contributors for their books of the year. Funnily enough, now that I’ve been asked myself, I am a lot less cynical about these than I used to be.1 But they are undeniably strange, in a way that should be familiar to anyone involved in publishing: you have to sign up to the fiction that the only books worth talking about were published in the last twelve months, when of course there’s no straight line between the year a book was published in and its relevance, let alone its quality.2 Many old books are painfully current. Plenty of new ones are out of date.

Bleak as the publishing industry often and increasingly is, especially for new fiction and poetry, I’ve got no great desire to trash it in toto. It’s true that relentless conglomeration and commercialisation across the supply chain - from publishers to bookshops - means you have to work harder to find the good stuff. It won’t be long before literary fiction goes the same way as poetry: not out the window, but out of the shop window, and we will lose more than we gain when that happens. And it’s true that there are a lot of bad books out there (I reviewed a few of them). But I also read a lot of perfectly good new books.3 They weren’t perfect, but then neither were most books published in 1956. Every generation gets the bad books they deserve and previous eras benefit from the halo of posterity distracting from the dross.4 The best we can do is try to support independent publishers and the authors still trying to navigate the machine.

All of which being said… the best books I read last year weren’t published in 2024. Here are a few that I’m still thinking about in December.

Bleak House, Charles Dickens (1853)

I’ve read Bleak House before, in the way that you vaguely think you have with Dickens. I enjoyed it even more this time. Perhaps I’m getting sentimental, but the more Dickens lays it on, the more I like it.

Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, right reverends and wrong reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us every day.

Then again, the most important (or at least, instrumental) character in Bleak House is Mr Bucket, who isn’t sentimental at all. Summoned up halfway through like a very practical fairy, Bucket quickly and efficiently strong-arms the plot into a detective story, arguably to the detriment of the final chapters. Because, as ever with Dickens, it’s the supporting cast that matter. Skimpole. Miss Flite. Mrs Jelleby. The Smallweeds &c &c and every one a warning. People complain that his characters are two-dimensional. Of course they are. So are we.

Bliss and Other Stories, Katherine Mansfield (1920)

Budding authors are always told to get their first lines right. Drop the reader in the action! Grip them immediately and don’t let go! The results usually reflect badly on the advice. We all know when a writer has designs on us. Being deliberate is particularly bad news for short stories, which are nothing if they’re not natural. The story has to walk through the door and walk you with it. And then there’s Katherine Mansfield, who does both:

And then, after six years, she saw him again. He was seated at one of those little bamboo tables decorated with a Japanese vase of paper daffodils. There was a tall plate of fruit in front of him, and very carefully, in a way she recognized immediately as his "special" way, he was peeling an orange.

Short stories are exercises in nerve. More so, perhaps, than poems. In order to establish both a narrative and a voice, the writer has to move between interiority and exteriority with reckless abandon, while remaining in complete control of their material. Few have, or had, more nerve than Mansfield.

The Holocaust: An Unfinished History, Dan Stone (2023)

This is an important and brave book. Stone is a serious scholar and chooses his words carefully but it’s difficult to come away without feeling that Holocaust education and commemoration has failed twice over: failed to communicate the true nature of events - which were, he argues, neither uniquely German nor uniquely “modern” - and failed to “draw the radical conclusions to which [it] should lead us” (my italics below):

…that the Holocaust was a deeply traumatic event for its victims; that the aftermath of the Second World War had not only positive consequences… but also incubated a dark legacy, a deep psychology of fascist fascination and genocidal fantasy that people turn to instinctively in moments of crisis and that the Holocaust not only reveals the fragility of the modern nation-state and the ‘pillars’ that support it… but calls their very organization and functioning into question.

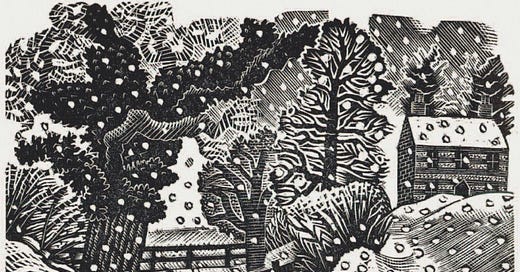

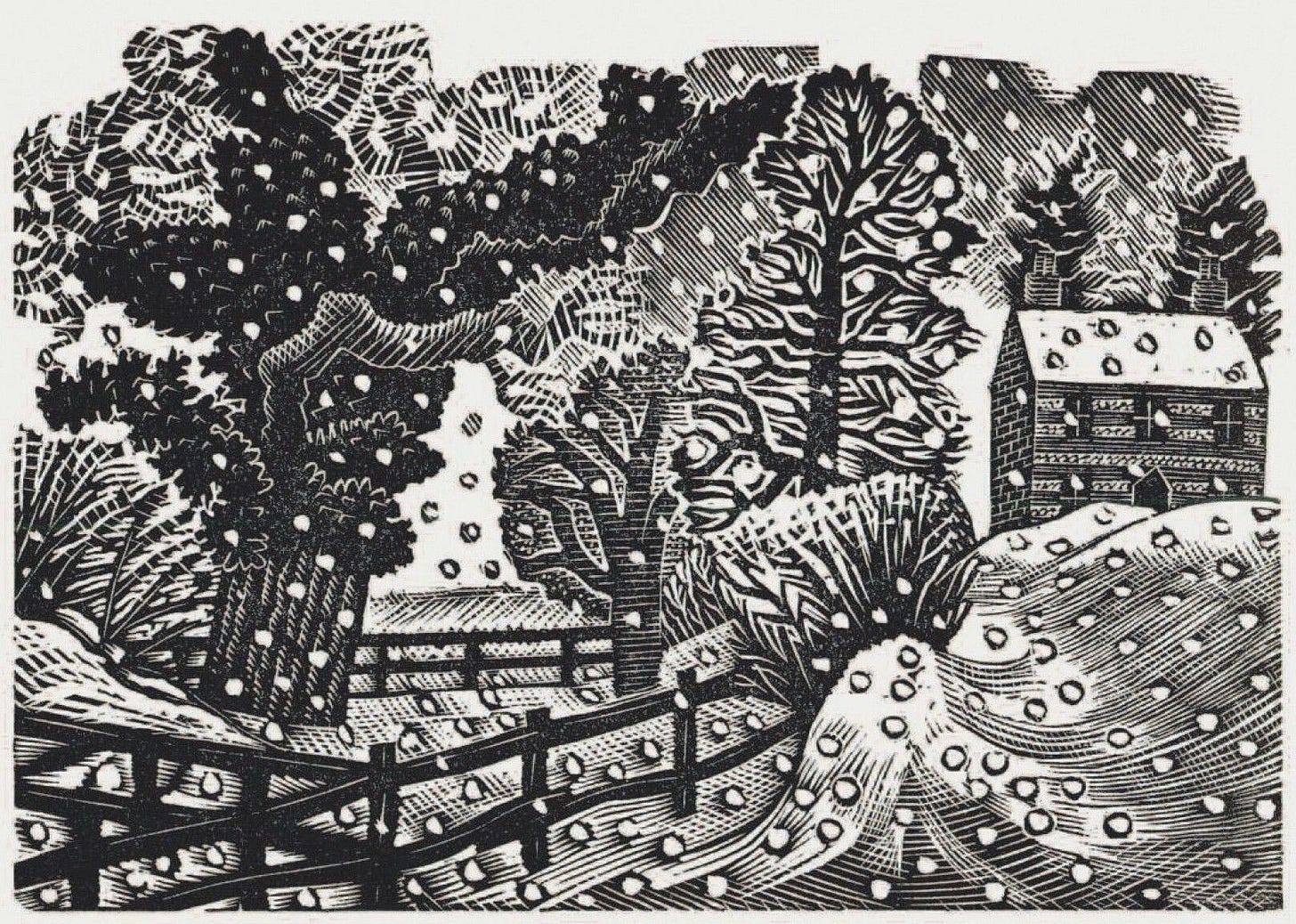

The Heart of England, Edward Thomas (1906)

...and beyond it an apple orchard on a gentle hill, and in the midst of that a farmhouse and farm-buildings so happily arranged that they look like a tribe of quiet monsters that have crawled out of the sandy soil to sun themselves…

This is one of the most beautiful books I’ve ever read, perhaps because I literally read most of it out loud in the evenings after our son was born. Thomas’s non-fiction - daring, neglected, genre-defying books which blur the lines between nature writing, short fiction, criticism, memoir and journalism, all in the most astonishing prose - are often seen as somehow preliminary to the poems. Wrong, wrong, wrong. The Heart of England isn’t in print, but you can get The South Country and In Pursuit of Spring from Little Toller Books.

Winter Recipes from the Collective, Louise Glück (2021)

The first of Glück’s collections I’ve read, though I knew individual poems. Also her final book before she died. The Nobel Prize win probably speaks for itself. I will just say that the way her poems climb down the page is uncanny. And they are testimony to just how hard - in every sense - so-called free verse and so called-confessional poetry is, or ought to be. This is the beginning of “Night Thoughts”:

Long ago I was born. There's no one alive anymore who remembers me as a baby. Was I a good baby? A bad? Except in my head that debate is now silenced forever. What constitutes a bad baby, I wondered. Colic, my mother said, which meant it cried a lot. What harm could there be in that?...

A Month in the Country, J. L. Carr (1980)

It is a few years after the end of the First World War. Tom Birkin, who has survived the trenches, is staying in a small Yorkshire village, restoring the church’s medieval mural. He gets drawn into local non-conformist life, falls in love with the vicar’s wife and strikes up a friendship with an archaeologist who’s digging near the churchyard and also happens to be a veteran. That’s it. It’s glorious. I can’t quote from it because I must have lent it or given it away, but that in itself is the best recommendation. Oh, and it’s summer. And Tom is writing all this a long time after it happened.

The lists are notorious for the trading of favours, but that probably shouldn’t discredit the whole enterprise.

One justification for literary prizes is that they slow down the publicity machine, if only for a moment. Ideally, they’d be awarded once every four years like the World Cup.

I probably wouldn’t read so much new fiction if I wasn’t getting paid to do it. Yet the more I read, the more frustrated I get with the (common) complaint that contemporary fiction is in a rut or that there is something uniquely wrong with the modern novel. I used to be the kind of person that said this, or at least suspected it. I also used to not read many new novels. The two things aren’t unconnected. In any case, here are some recommendations: About Uncle by Rebecca Gisler, in translation from Peirene, a deeply weird but engrossing experiment in disgust; All My Precious Madness by Mark Bowles, which I reviewed here; The Heart in Winter by Kevin Barry, which I reviewed, a little unfairly, here - Barry is a genius but I would start with Dark Lies the Island; Ordinary Human Failings by Megan Nolan, which is too-obviously-constructed but moving and convincing as a study of alcohol and addiction. The best new poetry I read this year, which happens to be by a friend, was Rowland Bagnall’s Ashbery-inflected, beautifully quizzical Near-Life Experience - like dropping your mind’s eye into a hot spring.

Lost and neglected masterpieces being the necessary casualties - but then we get the fun and the thrill of rediscovering them. I suspect that people demand more of new fiction (and new poetry) than they do of any other “media”. I suspect this is for one of two reasons, or else a combination of the two: because we read so few new books in the first place that those we do read are made to carry an unrealistic amount of pressure (as anyone who’s ever been asked to recommend one surely knows) and because by now we’re so spoiled by the canon that we have unrealistic expectations about what literary production actually looks like, year on year.

I feel quite excited that you included 'A Month in the Country', which I think poet Matt Merritt introduced me to many years ago. A wonderful book.

A Month in the Country is one of my favourite books - I reread it every summer.