Something almost being said: Larkin, Tennyson and 'The Trees'

Afresh, afresh, afresh...

I don’t have many poems by heart, at least not as many as I’d like. I feel that especially keenly now that I’m a father.1 But I do know this:

The trees are coming into leaf Like something almost being said; The recent buds relax and spread, Their greenness is a kind of grief.

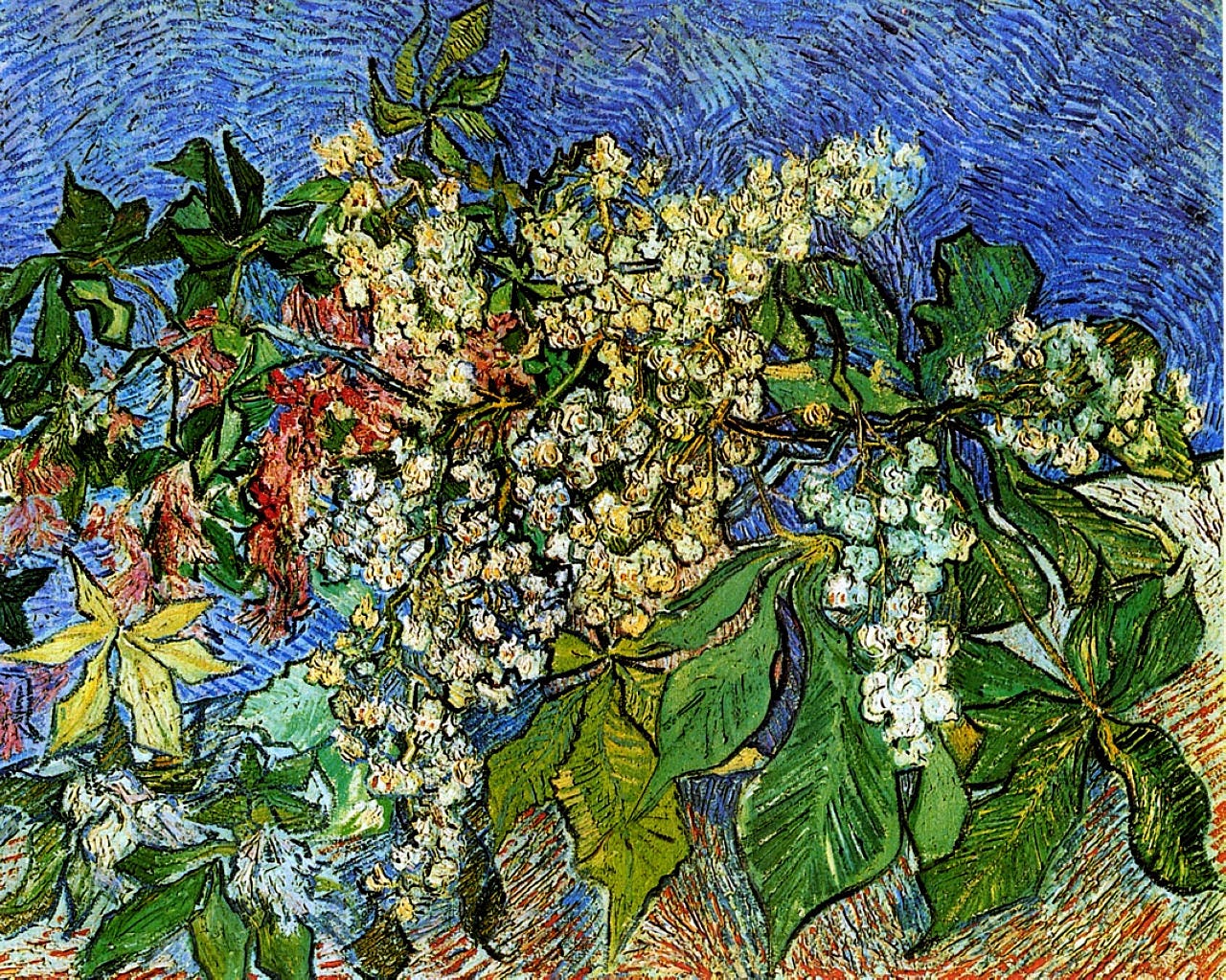

Larkin’s trees always arrive in my head this time of year, when London is lit up with gaudy chestnut candles. Partly, it’s that delayed rhyme, which isn’t as simple as it looks: it’s the same scheme as Alfred Tennyson’s In Memoriam. Tennyson haunts the whole poem. He’s there in the word “grief”, in the “greeness”, in those long, melancholy vowels.2

But it’s the image that’s unforgettable. Like something almost being said is a line which feels like it was always out there, waiting to be found. That’s what buds are like. It is also something only Philip Larkin could’ve written. There is something unnatural about. Buds bloom. Surely, something will be said eventually?

Archie Burnett’s edition of the Complete Poems includes a line from a letter Larkin wrote to Monica Jones while he was struggling to finish the poem:

“I seem to have spent a rather fruitless week, spending the evenings sleeping or starting at an incomplete & v. modest poem […] The poem is four lines wch I thought all right, then four more lines wch are less good; now I really want four more about as good as the combine best of Wordsworth & Omar Khayyam to sort of lift the thing up to a finish.”3

Larkin was unsure about it, then, as he was about everything . Elsewhere, he described The Trees as a “sixteen-year old’s poem about spring” and wondered whether it was possible to “write this sort of poem today?” Elsewhere again he says the first verse is “all right, the rest crap, especially the last line”.

Larkin is clearly being too self-deprecating. The letters to Jones are a way of geeing himself up (it must have been exhausting for both of them). However, it is true that the rest of The Trees doesn’t trip off the tongue as easily as the first verse/stanza. There is a kind of rupture, which is deeper than just a break between verses. The statement is called into question as soon as its made. Why is their greenness a kind of grief? Larkin raises the possibility that “we” might be jealous of the trees’ powers of renewal, only to discount the idea immediately:

Is that they are born again And we grow old? No, they die too, Their yearly trick of looking new Is written down in rings of grain.

Interestingly, Larkin’s earlier draft gave the opposite answer. This version, also given in Burnett’s notes, ends with a vision of the trees’ world as one in which:

A summer is a separate thing That makes no reference to the past, And may not ever be the last, And mocks our lack of blossoming.

But no, in the end the trees “die too”. In a sense, the final poem is a reply to the first version. This is Larkin thinking while writing, slowly and painfully. Rather than envy the trees’ (unreal) youthfulness, we should copy their lust for life:

Yet still the unresting castles thresh In fullgrown thickness every May. The year is dead, they seem to say. Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

There is something obviously, wonderfully daring about that last line. Either it works, or it’s one of the sickliest things ever put on paper. Mostly, readers think it works. Despite Larkin’s self-doubt, it is more evidence of his ability to know exactly what a particular poem needed. Here, a tree, waving in the wind.

So far, so familiar. We tend to read The Trees as Larkin at his most cautiously optimistic. It’s a poem in praise of spring. But this won’t do. There remains something sinister in Larkin’s foliage. That “trick” in the second stanza is one clue. The final stanza is Larkin at his most “Cavalier” (Seamus Heaney’s word), but there is also a kind of disgust or even horror here, both at the trees’ energy and their extravagance: “unresting” is uncanny.

Yet the ambivalence goes deeper still. The first stanza won’t be so easily forgotten. Like something almost being said is too strong, too leading an image. Even if we forget that early draft, the comparison which the poem originally sets up isn’t between arboreal and human lifespans, but between silence and speech. I can never read the rest of the poem without wondering what that something is. Why is greenness a kind of grief? Whose grief? We’re never told.

Looked at this way, everything that follows the first stanza a kind of distraction, a breaking off, almost an irrelevancy. The poem can’t answer the question, because the answer is already right there at the beginning: this is a poem about regret. Regret for words unspoken, a life unlived. What the whispering trees in the final line “seem” to offer isn’t so much hope, but another form of avoidance, a way to never really begin or blossom: move on, start over, give up.

It’s a whisper of temptation which the poem itself doesn’t entirely trust, even quietly undermines. Like Tennyson, Larkin is half in love with his own melancholy. He is also warning us against it.

Having not written much about poetry for a while, I haven’t been writing/publishing about much else recently. So it goes. I have a piece in Engelsberg Ideas about the poets of the Second World War (every bit as important as the poets of the trenches) and I’m also in the new Poetry Birmingham, writing in praise of a new(ish) collection by Rory Waterman.

Speaking of trees, I also have a new short story, “Kent’s Oak”, out with Fictionable. The story’s for subscribers only, but you can hear me talk about it (and trees) here.

I must have read this somewhere, but I can’t remember. Larkin reviewed a life of Tennyson in 1980, somewhat eerily: “Professor Martin has tried to be fair to Tennyson, neither making fun of him nor seem him, as his age did, as a figure out of Homer or even the Bible. The result is not a Great Victorian, but a personality at once dependent on others and inclined to neglect them, moody and sometimes panicky, close-fisted financially and emotionally and in every other way - except, of course, for the poems… It would be tempting to call this the life of a poet without his poems, if Professor Martin did not explicitly deny this in his preface. Nevertheless, it is the life of a poet without something, and perhaps poetry is the most convenient shorthand for it.”

Larkin is surely thinking of the version by FitzGerald beginning “Awake!”, which is another possible model for “The Trees”.

It's a good question about greenness and grief! Which got me thinking about my favourite bit of the poem: 'the unresting castles'. I wonder if this is one of Larkin's furtive recollections of once having enjoyed some French Symbolist poetry -- specifically, the poetic 'grief' of Rimbaud's 'O saisons, ô châteaux' (which is also about 'something almost being said').

YES, exactly, so much IMM:AHH in here.

The recent buds relax and spread,

Their greenness is a kind of grief.

If you make it anaphora here, you get Tennyson:

Their recent buds relax and spread,

Their greenness is a kind of grief.

This repeats in the poem time and again:

They have their day and cease to be:

They are but broken lights of thee,

Sleep, gentle heavens, before the prow;

Sleep, gentle winds, as he sleeps now,

And how my life had droop’d of late,

And he should sorrow o’er my state

etc. And anyhow, the idea of being 'almost said' is the keynote of Tennyson's grief:

"Could I have said while he was here" -- etc.