The task of describing something elegantly in verse is a difficult one, and success in it should be honoured. The poet’s main job, though, is to write about something.

George MacBeth

Poets like writing about certain animals more than others. Sometimes it feels like a question of proximity. Modern poetry (at least in the UK) is full of the pitter patter of tiny fox feet, presumably at least in part because of how often you encounter them in streets and gardens. There’s an irony in this. Foxes in poems usually represent the wilder side of nature. They are messengers from another world.1 I know one fox which spends half the summer sitting below the kitchen window of the same ground-floor flat on the way to the train station.

Children and babies like certain animals too (or at least we encourage them to), though they rarely encounter their favourites in person. For a child, the point of an animal is its distinctiveness. A fox might be a dog or a cat, but it is hard to mistake a koala for a giraffe. Animals are a kind of introduction to the world, in both senses of the word. They form a welcome party, snouts poking around the side of the crib: on clothes, in books, as toys, as hoods to their towels. But they are also a kind of way in to learning about… anything.

In the introduction to his Penguin Book of Animal Verse (1965), George MacBeth argued that the animal kingdom was the archetype of all subject matter. For MacBeth, this went beyond childhood: categorising animals was also the root of modern science, a cipher for the natural world. Animals are good for learning with because they are so ‘unlike each other’: real and unique in a way which is actually quite upsetting or overwhelming to think about for too long.

It is not by accident that children are taught the alphabet by means of associating animals with letters. Animals are instantly recognizable and never forgotten. Large numbers of them are quite unlike each other.

If poetry is a good introduction to animals, animals are a good introduction to poetry. The connection between animals and poetry in particular goes a long way back. Here is Paul Muldoon introducing the Faber Book of Beasts:

The very first animal poems (among the first poems of any kind) in most cultures must have been… hunting charms or spells, and something of their magical quality carries over into the earliest descriptions of animals in poetry in English…

Muldoon’s book would be a good place for anyone who wanted to read more poetry to start: animals allow for such a range of tones and approaches (funny, sad, grand, reflective). An anthology like this is also a good corrective to the widely-held and admittedly well-evidenced idea that poetry is navel-gazing.

MacBeth’s is the better anthology about animals. Muldoon’s choices often simply mention animals, rather than addressing them in any detail. It’s a good introduction to modern poetry because Muldoon stretches the theme to the limit in order to get the best poems in: Robert Lowell’s ‘Skunk Hour’ isn’t really about skunks. And there are less surprises than in MacBeth’s book, because Muldoon hasn’t done much thinking about the subject. He takes it for granted that animal poems are interesting because of what they tell us about ourselves.

By contrast, MacBeth argues that a good animal poem should be both about us and about the animal, which means the writer needs to know something about the beast they’re talking about. It’s a model anthology, in that the editor knows a lot about one subject and is passing it on.

All good poems about animals are about something else as well. It may be divine providence or it may be human iniquity. The important point is that these qualities should be seen through the nature of animals.

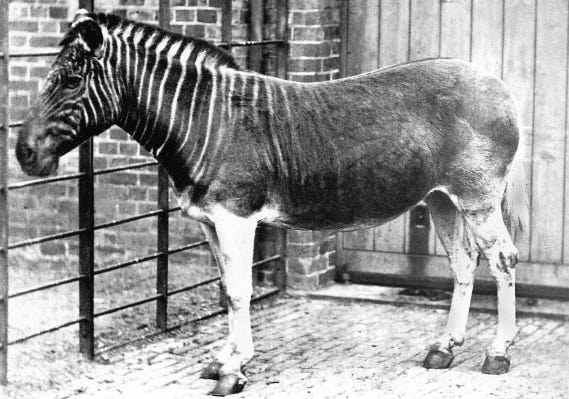

MacBeth is also a brilliant animal poet in his own right. His ‘Owl’ is a better Ted Hughes poem than any poem Ted Hughes ever wrote himself. The range of MacBeth’s references mean you get quite a lot of not-always-immediately-rewarding eighteenth-century verse, but he also includes some wonderful, sad and funny examples from his contemporaries, including Alan Ross on the koala (‘eternal / image of the cuddly bear’) and D. J. Enright on the last quagga:

By mid-century there were two quaggas left,

And one of the two was male.

The cares of office weighed heavily on him.

When you are the only male of a species,

It is not easy to lead a normal sort of life.

MacBeth helpfully distinguishes between three ‘ways in which poets have considered animals’, each of which he identifies with a broad historical moment. First, medieval poems, where animals are a source of information about God’s creation. These are morally and emotionally ‘neutral’: ‘it is the facts about the animal that matter’. Then, around the time of the Renaissance, ‘a more humanistic interest’ begins to appear. The poems are increasingly ‘normative’. The way animals behave, or the way in which we treat them, is a way of thinking about how we treat or should treat each other.

The modern animal poem, in MacBeth’s timeline, emerges in the ninteenth-century and finds its fruition in poets like D. H. Lawrence and Ted Hughes. Its defining feature is the use of individual and, increasingly, extreme emotion, ‘fear or rage for one’s own plight, compassion or hatred for the human condition’.2 For Lawrence, animals ‘buttress a whole theory of sexual energy’ while for Hughes the hawk in ‘Hawk Roosting’ is a portrait of ‘the psychology of extremism’.

When MacBeth writing, with the ruins of the Second World War still smoking, rage and hatred were more current than fear and compassion. These days the most common emotion Anglophone poets project onto animals is probably pity. Perhaps this shouldn’t come as any surprise; it’s hard to write about animals now without feeling sorry for them, which often means feeling sorry for ourselves even where our own actions have caused their problems in the first place. Sadly, pity doesn’t always make for very good poems. Larkin’s mole is a good example of the risks: his brutal internal editor melted in the face of the small and the furry.

At first, Sylvia Plath’s ‘Blue Moles’ seems like it might be in the same vein as Larkins. Plath finds two of them, dead:

They’re out of the dark’s ragbag, these two

Moles dead in the pebbled rut,

Shapeless as flung gloves, a few feet apart —

Blue suede a dog or fox has chewed.

One, by himself, seemed pitiable enough,

Little victim unearthed by some large creature

From his orbit under the elm root.

The confusion of scale in the mole ‘orbiting’ the elm is brilliant; tiny for us, its whole galaxy. But though the moles are pitiful, 'shapeless as flung gloves’, Plath neutralises the feeling by naming it. The first mole is ‘pitiable enough’ - a ‘little victim’. The ‘gloves’ and the ‘blue suede’ also help to prevent things from getting too maudlin. Violence is something that happens. Humans do it too, for example by making gloves (and notebooks) out of moles’ skins.

‘Blue Moles’ is in two, numbered sections. As the second begins, a transformation takes place and we seem to be about to take a very different turn:

Nightly the battle—snouts start up In the ear of the veteran, and again I enter the soft pelt of the mole.

Yet, almost as soon as she becomes the mole, Plath re-establishes the difference between them: they are moving through their ‘mute rooms’ (hard not to hear ‘mushrooms’ here) while she is sleeping. There is something psychoanalytical going on. The moles are war veterans with shellshock and Plath’s journey into the ‘soft pelt of the mole’ is a journey under the surface.

Light’s death to them: they shrivel in it.

They move through their mute rooms while I sleep

Palming the earth aside, grubbers

After the fat children of root and rock.

By day, only the topsoil heaves.

Down there one is alone.

In maintaining that difference, Plath makes both accounts more vivid and, in a strange way, only strengthens the connection between them. In MacBeth’s words, we see ourselves through the animal, but we also see the poem writing itself. By the time we reach the end, and the ‘moles’ have become insatiable (and arguably sexual) we are somehow reading two poems at once: that final, authorative, disconcerting, statement has nothing to do with moles, yet feels irresistable.

Outsize hands prepare a path,

They go before: opening the veins,

Delving for the appendages

Of beetles, sweetbeads, shards —to be eaten

Over and over. And still the heaven

Of final surfeit is just as far

From the door as ever. What happens between us

Happens in darkness, vanishes

As easy and often as each breath.

‘Blue Moles’ doesn’t fit neatly into any one of MacBeth’s categories: it moves between them, then moves beyond them.

MacBeth’s introduction partly serves as a defence of subject matter in poetry in general – ‘the twigs that make the fire blaze’.3 Perhaps it still needs defending. I’ve become pretty jaded. When I read that a new poetry collection is going to ‘explore’ this or that subject, I switch off. It’s easy to leap from there to the ‘art for art’s sake’ position, which treats the whole idea of subject matter as suspicious, somehow unserious. As if art were the only serious thing in life.

The problem with ‘subject matter’ in so much contemporary poetry isn’t the intention but the delivery. We spend too much time talking up poetry’s unique ‘way of knowing’ and not enough time facing up to how difficult it is to know anything in the first place, which would also involve respecting other ways of knowing, like history or science. Being interested in - or better yet, moved by - what a poet is interested in or moved by has always been as important to me as how they write. There is no reason why a poem about an animal, or family, or politics, or identity, or the person writing the poem - or about any of the subjects that critics sometimes complain that we hear too much about these days - won’t be a good or serious poem besides the fact that all of these things are hard to know. We are more in the dark than we like to think.

When Ted Hughes was a student at Cambridge, struggling with an essay, he dreamt a ‘burned fox’ entered his room. “Stop this,” it said. “You are destroying us.” In his defence, foxes didn’t really enter cities in large numbers until a few decades later. He was probably thinking back to his childhood in Yorkshire.

MacBeth suggests each mode is ‘equally valid’ so long as the animal itself is kept in sight, but everything he writes implies that this is harder to pull off in the third case. For Hughes and Lawrence, animals have been ‘conscripted into a private theology’.

“I am on the side of those who tend to like poems about dogs because they like dogs rather than because they like poems. Subject matter… has been derided too virulently and too long”.

Thank you for posting this Jeremy. Serendipitously, I was reading Hughes' 'Moortown Diary' just yesterday, continuously amazed at how brilliant this (lesser known?) volume is. I'm a big fan of Muldoon too and was reading 'Hoodie-Skelp' a couple of days ago. He was a strange choice though for an anthology on animal poems. I must get a hold of the MacBeth book.

Thanks for reading (and for the recommendation)! You're right, a strange choice, though he does write a few himself.... I'm sure there's a few second hand copies of the MacBeth knocking around - I have a huge weakness for those paperback Penguin anthologies.