It’s tempting to approach “Ozymandias” as a kind of relic, like those two vast and trunkless legs of stone standing in the desert, a monumental poem we might poke around out of a sense of duty but which doesn’t really speak to us. Critics, like tourists, have a habit of visiting things because they are there.

But the poem does, literally, speak. Reading it again the other day the first thing that struck me was the number of different voices involved. “Ozymandias” is a kind of Russian doll, reported speech enclosed within reported speech:

I met a traveller from an antique land Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert . . .

The ‘I’ who opens the poem is dispensible: they get ten words. Two words into the second line, someone new is already talking. But no sooner has this traveller mentioned Ozymandias’ legs than he’s talking about the statue’s ‘wrinkled lip’ and ‘sneer of cold command’. We can already see this ‘shattered visage’ moving its mouth, alone there in the sand, like something out of a cartoon. And this is all before we get to the famous words engraved on the pedestal.

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

The poem’s closing lines are, in theory, given to the traveller, but the lines on the pedestal serve to cut them off from the rest of the text. So, it’s easy to imagine the conclusion as yet another voice, or, perhaps, as no voice at all.

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.

All these different voices jostling for space make “Ozymandias” surprisingly difficult to read out loud for a poem which is often taught and celebrated for its simplicity. True, the language is more natural than you often get with Shelley (Shelley is either as crisp as an apple or completely unreadable). You can’t recite it ponderously like some readers imagine old poems demand you do, because the register is always changing. The variety of surfaces crushed into the square block of a sonnet give the poem a kind of glassy quality. Like a hunk of granite.

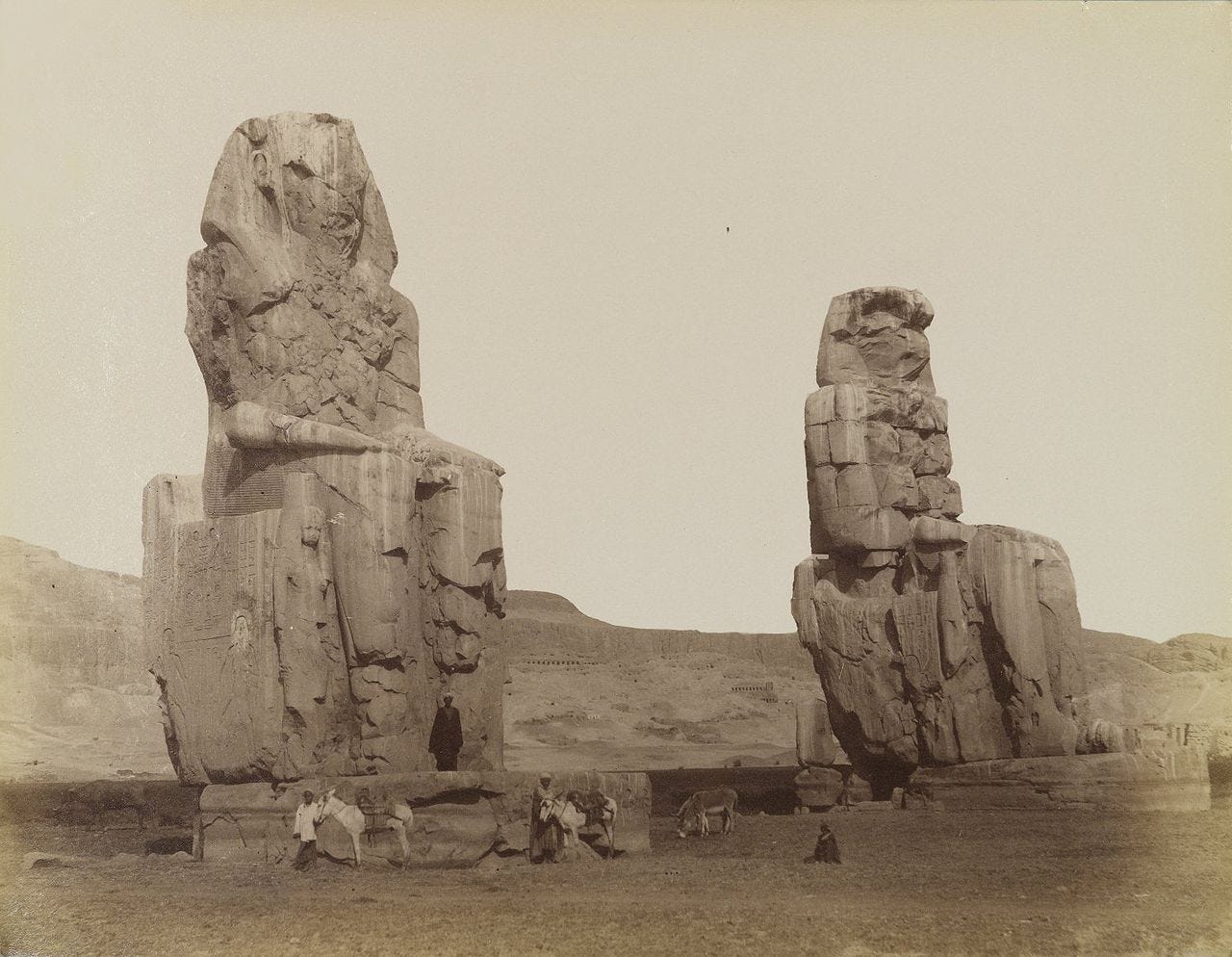

Content-wise, “Ozymandias” is often talked about as a comment on Victorian hubris. It was written as part of a friendly competition with another poet, Horace Smith, whose own quite bad version goes on to describe a hunter making their way through the ruins of a future London, a dreamscape which was probably as familiar to Victorians as post-apocalyptic New York is for movie-goers in the States. Shelley was also inspired by reading about the ‘Younger Memnon’, a collosal head which originally formed part of a temple complex in Luxor. The British Consul in Cairo was shipping this head back to the British Museum at the time. There is no evidence Shelley had actually seen it.

When the Victorians imagined the remnants of the ancient world, they saw a warning for their own future: the poem, on this reading, mocks Ozymandias’ pretensions and by implication our own.1 Ozymandias’ ambitions are compared unfavourably with the sculptor’s: unlike the rest of his mighty works, the King of King’s shattered visage is only ‘half sunk’ and yet, through the sculptor's skill in manipulating 'lifeless things', curiously and terrifyingly alive. Art (and by extension, poetry) wins out over tyranny.2 “Despair” is ironic.

Yet Ozymandias’ works do survive. Here we are talking about them. That’s the thing about words etched in stone. It is why ruins have such a hold on the imagination in the first place. They persist. Ruins speak and go on speaking, from the writing on huge public monuments in Rome to private gravestones or roadside waymarkers. More words are written today than ever, but it’s still possible the future will remember our ancestors better than they remember us.

What survives in ‘Ozymandias’ isn’t art in its own right or art alone, but public art, monumental art, art which has found a powerful patron willing to give it a plinth, and cough up the cash for the hard materials. Good stone is, after all, pretty expensive. So is lugging it about. In the end, Ozymandias and the sculptor need each other. There’s an awkward lesson here somewhere, if we want it.

Ozymandias is often associated with another collosus, which is still in the Ramusseum, lying on its side. The Ramusseum is one of the most incredible ruins I have ever seen, in part becauese when I saw it, in March 2011, we were more or less the only tourists in Luxor. In retrospect, the last lines of the poem could also read as a comment on what the Near East looked like after the Victorians were done filching the antiquities.

There is, if you think about it, another poet in the poem beyond Shelley.

Thank you for writing about this. I love Ozymandias, and it's always made me like Shelley far more than I otherwise could have, but for some reason I've never fully noticed all the different voices. You've made it come alive for me in a whole different way. Beautiful mini essay.

Have you heard Bryan Cranston as Walter White recite Ozymandias? Cool, very Todd Hido-esque (Todd Hido the American photographer) video with the natural beauty of New Mexico and the decay of Albuquerque.