In February 2022, my girlfriend and I quit our jobs and went travelling through Italy, Greece and the Western Balkans. Times were still a little strange (they still are). Europe was coming out of the pandemic. Those years all roll into one in my memory and I still have to double check the dates when I think back, which is presumably some kind of trauma response. I do remember a lot of uncertainty about crossing borders. The places where we were ultimately heading didn’t ask for much by way of proof of health and vaccination, but to get into Europe to begin with you needed a very recent negative test, so we schlepped over to a pop-up “clinic” in the most miserable part of Southampton to stand in a dense queue and pay a silly amount of money to let a couple of what-looked-like teenagers swab our noses. When we arrived at the airport in Rome the next evening, no one asked to see any tests or vaccination cards. There was barely anyone there at all.

I love Rome. I love almost every Italian city I’ve been to but I love Rome especially. Somewhere so old and so serious and so national has no right to be so easy to love (I love London too, but it isn’t easy to love). Perhaps this is something to do with Italy’s history: for a long time after the Romans, Rome wasn’t the political capital of anywhere at all. Mostly, though, I think I love those red rooves resting between the hills, like potpourri in a wide, shallow bowl. Every view gives a sense of plenty, but a plenty that’s close at hand. The rooves might go on for ever, but they are also contained, limited, maneagable. Walking around at street level is the same. There is always something to see, but unlike Venice or Florence I never feel like I have to see everything. It’s rich and deep without being overwhelming. Which, incidentally, is also true of the best Italian food.

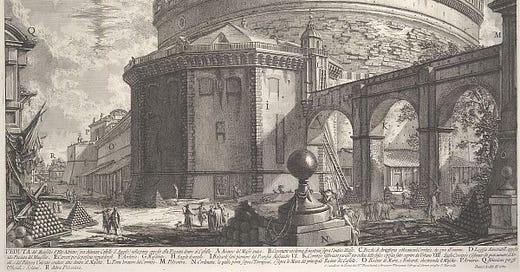

One of my highlights from this last trip was a place I hadn’t bothered with the first time, a strange, squat, rotunda on the river up by the Vatican called the Castel Sant’Angelo.1 The Castel is many things. It looks like a rather uninspiring, fortified cake. It is now a museum. It is described on all the maps as just that, the Castel Sant’Angelo. But it is none of those things, underneath. Underneath, it is the Mausoleum of the Roman Emperor Hardian.

Maybe I love Rome because I love layers. All that history on top of itself. To a certain kind of sensibility, the only thing better than a ruin is a ruin leaning against an older ruin. After the fall of the Roman Empire, generations of popes fortified the Masoleum out of all recognition. At the top, there are elegant little private apartments with shamelessly pagan decorations. But to get up there, you have to climb up through the tomb itself.

I found this quite overwhelming. The original decorations - the marble walls, the bronze and stone statues - are all long gone, so what’s left is a large, bare brick cylinder (you can see the sides, beneath the crenallations, from the river). In order to use the building for military purposes, the popes constructed a huge stone ramp right through the centre of the cylinder. As you climb this ramp, you are climbing through the space above the Treasury Room, deep in the heart of the building. This is where Hadrian’s urn was originally placed and where the urns of many subsequent emperors joined him. There are funeral niches for relatives in the walls, all empty now too. Like the decorations, Hadrian and the emperors are no longer there. The Visigoths probably scattered their ashes in 410, when Alaric sacked the city.

Instead, almost exactly halfway up the ramp (if I remember right) there is an information board, which includes a copy of a famous poem attributed to Hadrian, written as he was dying of a long and unpleasant illness. We know the poem because it was quoted in the Historia Augusta. Hadrian was particularly interested in the arts (the Historia says he used to pursue arguments with “philosophers and professors” through poetry) and I can’t see any reason not to think it was his. The original Latin goes like this:

Animula, vagula, blandula Hospes comesque corporis Quae nunc abibis in loca Pallidula, rigida, nudula, Nec, ut soles, dabis iocos.

I don’t read Latin. I took it for a few years at school and then dropped it because I wanted to carry on with both Ancient Greek, which I now can’t read, either, and Drama and I wasn’t prepared to do an extra subject.2 But I can hear it, more or less, and I can hear that lovely, tripping rhythm, which is clearest in the first and fourth lines but present throughout, and which is one reason why the poem has been so popular among translators. W. S. Merwin called it ‘flawless and haunting’.

For a poem so perfect, there is little consensus about how to translate it, so much so that I can’t offer a standard version. Below is a version of the poem I published last week, in the latest issue of The AI Literary Review. I made it when I got back from the trip, by putting each line, one at a time, through Google Translate.

Sweet soul travelling Host and companion of the body You'll end up in that place Pale, still and naked Not laughing as you usually do

There are some pretty serious issues with this “translation”, which we’ll get on to in a moment, but I like it.3 The idea behind taking each line individually was to sidestep the main problem translators face: how to ascribe the adjectives in the fourth line? Pallidula, rigidia, nudula. For some translators, these three words refer to Hadrian’s soul, for others, they belong to the place where the soul might end up and for others still they should be distributed between the two.

The other main problem translators have to tackle is how to punctuate the third line, which (the first serious issue with my “translation”) should really be a question: not you’ll end up in that place but where will you go, now, little soul? That question must in turn be why so many have assumed that the adjectives belong to the place. What kind of place does a soul end up in after death, if you are a Roman? A pale, quiet and cloudly place. (The other serious issue with my translation is that nudula does not mean “naked”).

I find the other approach, the one which ascribes the adjectives to the soul, more convincing and also more attractive. So much of the appeal of the poem is in the pity Hadrian displays for his soul after death, right from that first line (animula is anima, soul or life force, in the diminuitive). W. S. Merwin’s translation, which is my favourite, makes a great deal of the pity. Merwin also plays with the lines:

Little soul little stray little drifter now where will you stay all pale and all alone after the way you used to make fun of things

Merwin calls this translation ‘as literal as it could possibly be’, which strictly isn’t true - the second line of the original has gone missing! - but I think it captures the spirit of the original better than anything else I’ve read. It’s spare and austere, gentle and sad. Merwin also avoids the question mark.

Still, I also didn’t want to discard the possiblity that Hardian is describing something else. The poem lives in that ambiguity. The effect of that fourth line, detached as the words are from either the soul or the spirit world, is conjour up a ghostly image of something else again. Namely, the body.

Hadrian’s soul, after all, can’t be entirely rigidia if it is also on the move and why would it be pallidula if it no longer has a body? At the same time, it makes perfect sense to think of a soul as being somehow stuck without the body which gives it motion. Though we’re accustomed to think of souls as a kind of animating life force, we also think of them of shades: pale and bloodless shadows. What’s left after reading this line is neither the soul, nor the underworld, but what both those places are missing. The image of the little, wandering soul is pitiful because it is an image of a poor, wandering person, dead or alive.

This also gives a new answer to Hadrian’s question. The place where the soul ends up is the place where the body ends up, because soul and the body are one: not the underworld but the tomb. An urn, perhaps a mausoleum.

This in turn helps to answer the question that has been bugging me about my ‘AI’ translation. When I put pallidula rigida nubila through Google now, it gives me “pale, stiff clouds”. Nubila might mean cloudy weather, it might mean a cloudy, melancholy mood. What it doesn’t mean is naked. Did I write it wrong in the first place? Did I think “nude” when I read “nubila”? Did some kind of ghost get into the machine? Someone was thinking about bodies.

The other license my own translation takes is that it doesn’t simply remove the question mark, like Merwin’s, but gets rid of the entire question. As with “naked”, I don’t remember doing this deliberately. I’m sure Google did it, though again, as with “naked” it doesn’t do it any longer. Again, I quite like whatever’s happened here, though I think if I “wrote” the poem again I would do it differently. We know, by now, where Hadrian’s soul ended up: its tomb stripped bare, hidden in plain sight and trampled by tourists, some of whom go on to put his words through faceless algorthims. But we don’t know where his ashes are.

I have been to Rome twice and not seen the Sistine Chapel. I have been to Paris several times and not been inside the Louvre. This is probably the misplaced confidence of youth and I will regret it one day. But if you’re only there for a few days, why spend half the day in a queue?

They made us take three sciences at GCSE. I am not bitter. I am over it.

When I first ran the translation, the debate about the threat AI poses to writing and art hadn’t really gone mainstream. Would I feel differently about doing it now? Probably not. I think this is a relatively harmless exercise, even if Google has ripped people off to get here. And perhaps poetry is one place where an engine like Google Translate might really help and even encourage readers, as little consolation this might be to the people whose work and knowledge has been ripped off.

I finished reading Marguerite Yourcenar's Memoirs of Hadrian about a month or two ago and absolutely loved it, and she takes some of her section headings from this poem. It's really interesting to see the Google translation version, and I love W. S. Merwin's version. Thank you so much for sharing!