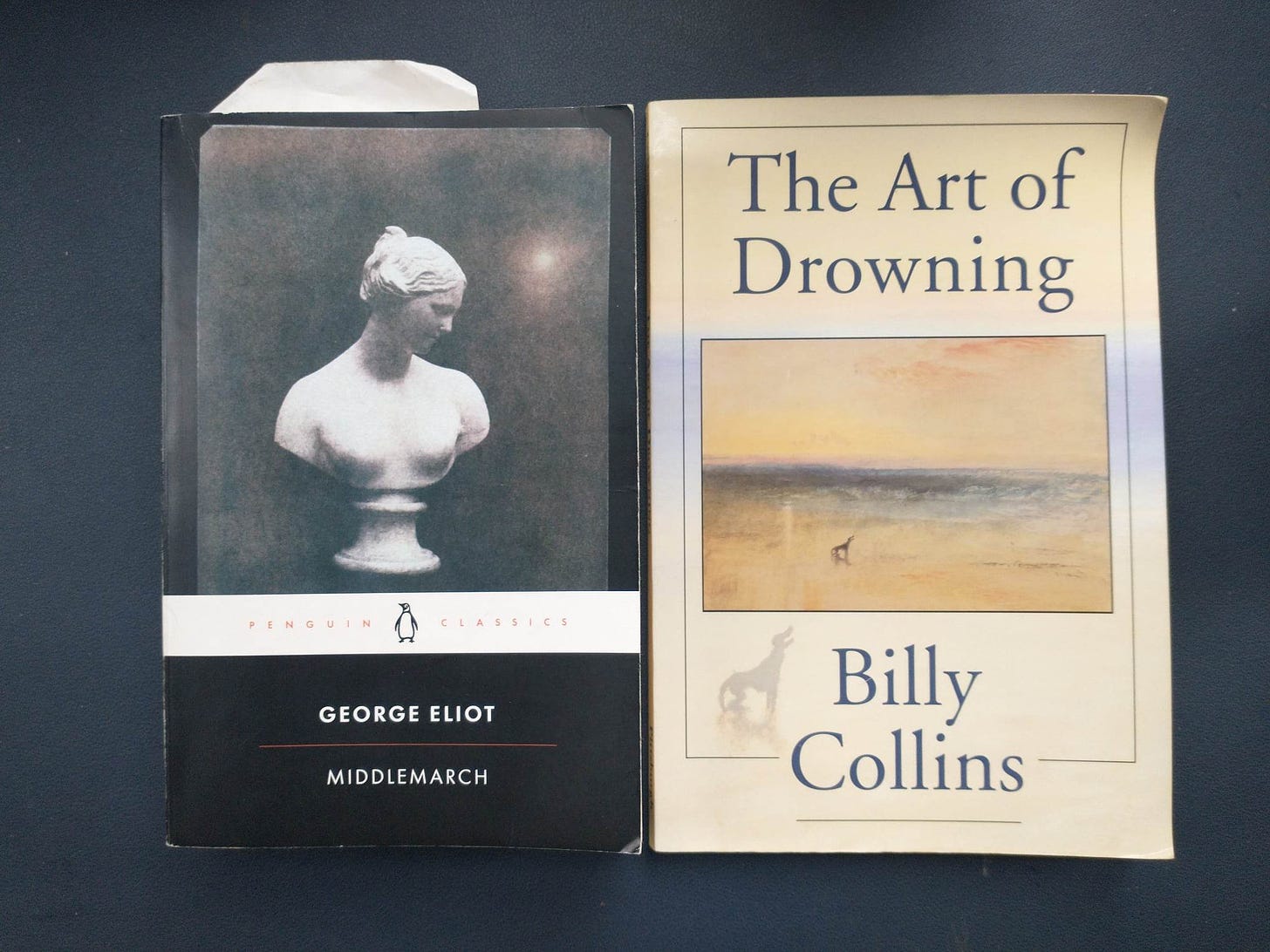

Around this time last week I read a Billy Collins book cover to cover for the first time. The cover itself, which is pretty awful, involves a Turner painting, and the second-hand bookshop where I found it was tucked away in the stables of a National Trust house full of Turners, so I took that as a sign.

Anyway, I enjoyed it. A lot. It got a bit repetitive by the end but that wasn’t the book’s fault - you’re not supposed to read these things in one sitting. There is a kind of playful, metaphysical inquiry going on, a rapture of Things and Experiences. There are some good jokes, too, and a pervasive, endearing sense of irony. I’ve not read much Collins, but I feel like I have been reading about him for as long as I have been interested poetry. I knew, for instance, that he was pretty popular among ‘ordinary’ readers for a poet, and (funny how the two go hand in hand) often disdained by poets, or people who read a lot of poetry.

Collins’s critics (his critical critics) object to how ‘prosaic’ it all feels. The lines are superficially so simple - so steady you hesitate to call it a rhythm. Each poem settles into a set line-length which may or may not have something to do with meter and is rarely varied. This, as much as anything, is why I tired towards the end. Yet that steadiness – let's call it a pace – also creates the terms on which you encounter what Collins is actually delivering. The lines are a kind of high-wire act. Once he has started with them he has to keep going, and they wouldn’t work if he broke them anywhere else. But they are not the main show.

I am now going to introduce the first of several associations which come solely from recent reading and otherwise have very little justification. Collins’s poetry reminded me of the kind of poetry the poet/critic Donald Davie advocated for in his book Purity of Diction in English Verse. One of the primary aims of poetry, Davie contends, is to tread a line between heightened language and the sober language of prose.1 Prose is conversational, but it is also restrained: it values accuracy and intelligibility. A Collins poem leans a long way toward prose. But prose, for Davies, has its own virtues.

In ‘The Thesaurus’, for instance, Collins ends with a kind of poetic manifesto:

I would rather see words out on their own, away from their families and the warehouse of Roget, wandering the world where they sometimes fall in love with a completely different word. Surely, you have seen pairs of them standing forever next to each other on the same line inside a poem, a small chapel where weddings like these, between perfect strangers, can take place.

There are few words or lines here which shout ‘this is a poem’. But it is the plainness of Collins’s diction and the way the metaphor builds throughout the stanza which allows him to finally retrieve the loveliness of that combination – ‘perfect strangers’ - to make the phrase unfamiliar and beautiful again. You only achieve effects like these by letting a little bagginess in.

When I first read this poem I thought the ‘pair’ of words being referred to was weddings and strangers, which wouldn’t work because they are on not on the same line, though they are, for what it is worth, on a vertical line. Everyone who marries someone is marrying someone who was once a stranger. If we’re lucky, we also marry someone who is perfect.

Now for the second questionable association. I spent the rest of my week off reading Middlemarch for the first time. I haven’t finished (no spoilers) but it has already been a revelation, like coming across an entirely new genre. So much of Middlemarch is poetry. George Eliot always finds the right word or metaphor. It is not simply the brilliant characterisation or the psychological insight – it is the exquisite descriptions. This one of procrastination, for instance:

“…the hours were each leaving their little deposit and gradually forming the final reason for inaction, namely, that action was too late”.

At one point in the novel, Will Ladislaw, a young, poor-ish writer, offers a definition of poetry to the unhappily-married heroine he is in love:

“To be a poet is to have a soul so quick to discern, that no shade of quality escapes it, and so quick to feel, that discernment is but a hand playing with finely ordered variety on the chords of emotion – a soul in which knowledge passes instantaneously into feeling, and feeling flashes back as a new organ of knowledge.”

That paragraph is everything it describes.

It is also a definition of poetry which could only have been written before modernism. Form, which we spend so much time worrying out now, doesn’t come into it.1 Poets today often describe their medium as ‘intense’ language, where that intensity consists of individual word choices or word-music. On this theory, poetry is prose with the amp turned up to 11. Whereas, to Ladislaw it is obvious that what makes poetry poetry is metaphor. Metaphor is the heart of poetry, troubling the line between thought and feeling.

Perhaps this is all obvious or should be obvious. I am only just beginning to see it clearly, possibly because it is too obvious to see, possibly because I find metaphors don’t come easily in m own writing. I don’t think they come easily to contemporary poetry, full stop. It is quite normal to read poems which don’t use them.2 While writing this, I flicked through a few recent collections. I found more metaphors than I was expecting, but they were mostly modest, scattered and rarely integral to the poems or confined to adjectival constructions. There was none of the extended scaffolding you get with Collins (or Eliot).

Metaphor is risky, especially an extended metaphor. Sometimes I feel like a distrust of metaphor is the defining feature of contemporary poetry. If this is true, it goes right back to modernism and the revolt against (terrible mixed metaphor incoming) the debased coinage of flowery Victorian verse. It has something to do with modern conditions, too – alienation from things, transitoriness, the destruction of old certainties. All metaphor is a kind of dance between an individual’s sensibility (I think this is like this) and what can be expressed in language: what you can risk depends on how far you trust your audience to make the leap with you. But modern audiences, where they exist at all, are necessarily unstable, uncertain, unknown. Davies knew all this in the fifties.

Instinctively, I know poems need metaphor even as I shy away from it. It can be tempting to squeeze one in at the end, in the same way that many unrhyming poems close on a rhyme. This - the closing image where there’d been few images before - is also something you see a lot in contemporary poetry.

Collins’s metaphors need room to roam. Almost all the poems in The Art of Drowning are two or three pages long. In ‘The End of the World’, another poem which is also a poem about metaphor, he casts a sceptical eye over the usual fire and brimstone accounts of the world’s ending, the ‘gaunt, bearded’ preacher holding up ‘the news he cannot keep / to himself’. By the end of the poem, Collins finds he has become a similar figure to the preacher. What he calls in is not the end of the world but perhaps the closest thing we know:

Now it’s me down on the floor lettering my sign proclaiming that daylight is drawing out of the sky. This is the message I will carry down the gauntlets of the city, my eyes hollow like those of the dungeoned, the shipwrecked. Soon it will be evening, and a fuller darkness will descend, just as I have prophesised, and then, according to my warnings, we will behold the starry-eyed messiah of the night.

Books mentioned

The Art of Drowning, Billy Collins

Middlemarch, George Eliot

Purity of Diction in English Verse, Donald Davie

Form in modern poetry is like money in the Henry James quote: a worry, whether you have it or not.

It is quite possible to write a good poem without using metaphors or similies, although often that means that the poem is the metaphor.

“Metaphor takes us from a precise somewhere to a diffuse nowhere” - Louis Zukofsky. The best Pietry eschews metaphors and similes…