Who owns the sky?

Condensation trails, conspiracies, and strange, fish-shaped craft

The other morning the sun wasn’t quite up and the sky was navy and cloudless, though not entirely - there were condensation trails overhead, more than I thought was usual and many in the moment of formation, squeezed out of small, fish-shaped craft like toothpaste from a tube. Perhaps something unusual had made me notice them, though it might only have been the cloudlessness, which besides ensuring the trails are visible in the first place also invites you to look - really look - at the sky: suddenly, there is something to see other than a leaden grey blanket. There are no huge cloudscapes in February, no tottering towers pinned in place or scurrying sideways; it’s thick sheets or nothing.

The night before was also cloudless and we’d stood in our little backyard behind the houses and tried to make out the constellations beyond the streetlamps. I was surprised by how many stars were visible. I’d thought it was London’s light pollution, not the cloud cover, which hid them. There was Orion and his belt, there was the Plough, and some kind of triangle, something red (a planet?) and at least four of the Pleiades. “The stars are a free show”, one of Orwell’s tramps says in Down and Out and Paris and London, “it don’t cost nothing to use your eyes.”

The sky is a free show, but it’s been a while since it was free from human interference. A little later that morning, opening the blinds, the view across to the further hill was perfect: silhouettes of skeletons of oak and beech on the ridge, and the odd block of flats, both black against a washed-out yellow grapefruit morning. From here, I could no longer see the longer contrails. Instead, either side of the telephone mast which dominates the skyline (quite benignly, unless it’s shrouded in mist and flashing its one red eye), there was a short, pink dash: a distant trail truncated by the perspective, lit beneath by the rising sun like a very careful dab of paint. Pink on yellow.

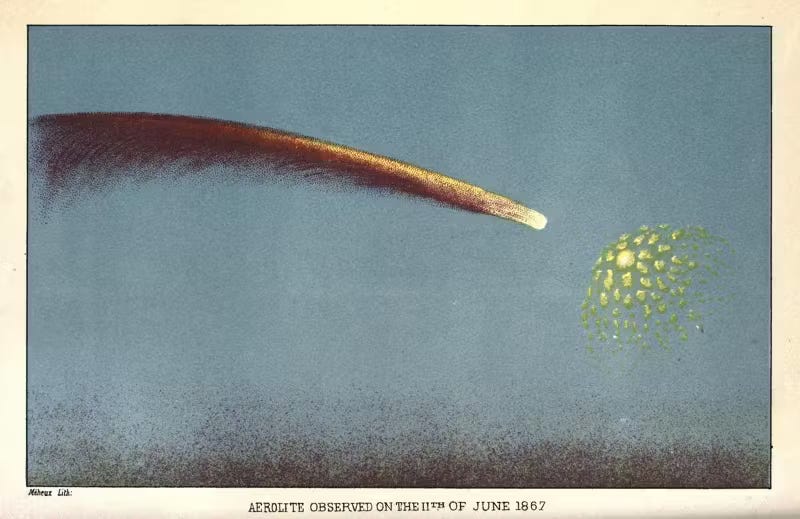

Once upon a time the sky was otherworldly. Now, it’s just another sphere of human activity. I must have read countless articles about the deplorable quantities of space junk in earth’s orbit. And I can see why litter in space captures the imagination - why it would make our colonisation of the clouds old news. But surely our outrage has skipped out a stratosphere. Celestial spaces were always hard to picture and still are for most of us. But the sky was common property, a familiar other. No one chose what was in it, except perhaps God. Now, unless you live in the middle of nowhere (and even then), someone has chosen what you see above your head and you had no choice in it - even when, occasionally, it can be beautiful. The more I think about it the stranger it seems.

As far as I know, that shift happened almost entirely without discussion: if there was serious opposition to aviation, it would be a great story in itself. Now that it’s happened, it goes without comment. It takes a very particular combination of circumstances for me to notice how busy the sky is (I realise now that one reason being away from London feels so peaceful is that there’s less going on above me). That morning, I suppose was also thinking of the recent decision to expand Heathrow, which was where the planes were coming from, as well as the series of planes dropping from the sky in the US and the fragile ceasefire in Gaza.

As every psychoanalyst (or probably anyone over the age of thirty) knows, when we ignore something, it doesn’t disappear but resurfaces elsewhere. The busy sky is the breeding ground of some of the most popular and persistent conspiracy theories: the UFO craze takes off around the same time that commercial and military flight really picks up in the States (there is a curious map somewhere which demonstrates that aliens have a strange preference for abducting people in the wealthy, plane-oppressed West). Simplifying wildly, the phenomenon feels like an obvious sublimation of the fact that there is anything in the sky at all. We are the aliens and always have been. In recent years, a whole industry of conspiracy has also built up around condensation trails: the streams are supposedly controlling the weather or else dropping chemicals which placate the populace. The UK government maintains a set of “frequently asked questions” online, which is surely a (not very subtle) attempt to tackle those “concerns”.1

The social-psychology explanation for the rise of conspiracy theory is probably a little too charitable: show me a conspiracy theorist with a big following and I will show you someone making a profit (including on this website). Yet it must, in part, explain why they spread. After all, why is no one talking about things in the sky? This is hardly a new observation. These theories offer a way of dealing with the fact that in the modern world so many things just happen, or are done to us, without anyone ever stopping to explain or justify them. Who owns the sky?

Of course, we don’t talk about the things in the sky because they are completely ordinary. Toddlers will spot planes as easily as they spot birds, often at a far greater distance and sometimes when the plane is so small and so quiet you can barely believe they’ve noticed it, barely believe that it’s there. Of all the things to see! But, of course, they don’t know any better.

In John Wyndham’s post-apocalyptic classic The Chrysalids (easily his best book) the narrator David grows up in a blighted place without any knowledge of modern technology. Towards the end, he describes his first encounter with a flying machine. The confusion is perfectly realised, and deceptively simple: when I first read it, I was sure it was a spaceship.

“I looked up, too. The sky was no longer clear. Something like a bank of mist, but shot with green iridescent flashes hung over us. Above it, as though through a veil, I could make out one of the strange, fish shaped craft I had dreamt of in my childhood hanging in the sky. The mist made it indistinct in detail, but what I could see of it was just as I remembered: a white, glistening body with something half-invisible whizzing around above it. It was growing bigger and louder as it dropped towards us.”

Science fiction, at its best, is a way of seeing a present that moves too fast.

It doesn’t help that they genuinely did subject people to germ warfare trials during the Cold War. It didn’t know this until I looked it up.

Totally agree about The Chrysalids!

I love 'The Chrysalids'.