If you have, or have ever had, a baby then you will probably have picture books. Pictures books these days are often very beautiful and increasingly intricate. Our baby is seven, almost eight months. He likes to turn the chunky cardboard pages. He also likes to gnaw at their spines. Some of the best ‘books’ for babies aren’t really books at all but collections of fabric swatches, though this too is a reminder that books are objects before they are anything else.1 All this is, it turns out, a relatively recent phenomeon: large picture books, Sam Leith notes, “now represent the average child’s first reading experience” but they are a result of new technology and “the increasing ease… of printing”.

My review of Leith’s recent, very enjoyable and very perceptive “history of childhood reading” is up on Engelsberg Ideas here. I could have gone and on, but my editor was already being generous and I wanted to focus on the question of what makes a book a children’s book in the first place.

So, for instance, I didn’t mention Leith’s brilliant reading of the horror of Beatrix Potter. Horror might seem a strong word but I think it’s the right one, for Potter particularly, but also for the experience of being a child in general. How terrible it must be to be so small. I’ve been wondering recently whether “horror”, the genre, isn’t itself partly a hangover from infancy. Do adults get a perverse pleasure out of books and films that set out to scare or disgust them because it reminds them of being young? Maybe Freud had something to say about that.

In Potter, as in a lot of children’s books, the horror lies in precisely what makes them childish: their attention on food and animals. These are the safest thing in the world—if you have or have had a baby, you will also be surrounded by animals—and yet the child must learn, pretty early on, that her animals eat each other and that she eats them. As Leith shows, Potter’s creations skip between the human and the animal world with disturbing ease. Potter has a “doubleness of eye”: she was a botanist before she was an author and illustrator. Sometimes her badgers eat wasps, frogs and worms, but they will eat rabbit pie “when other food is scarce”. The fox wants to eat Jemima Puddleduck, “but he makes her fetch herbs and onion so that he can eat her in the manner a human would eat her.” Later on, some puppies eat her eggs, “leaving her in tears”.

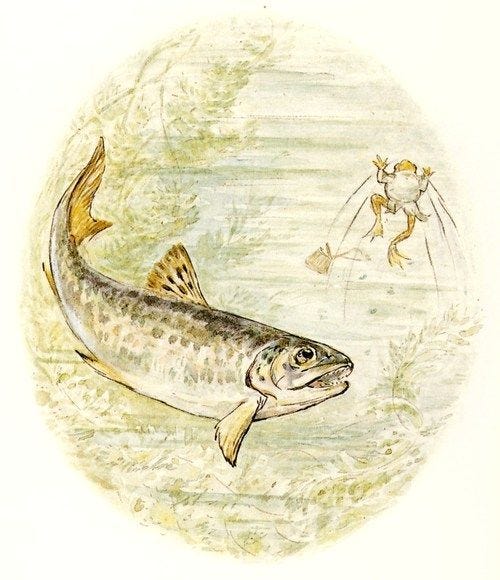

Perhaps all horror is bound up with eating and being eaten. As a child, I remember identifying very strongly with Jeremy Fisher, the rather hapless frog from The Tale of Jeremy Fisher. I also had a recurring nightmare in which I was suspended in a murky pond, about to be swallowed by a very big fish. I knew that whatever it was, it would be the end. Then I woke up.

Sadly, I don’t get any money if you buy something through this link.