These close readings are settling into a monthly rhythm. I am very grateful for all the encouragement so far, not to mention the insights in the comments (especially the insights in the comments!). I would like to do them more regularly. I would like to branch out into some more unfamiliar poems/poets. Subscriptions are a great encouragement too.

The Bean Eaters is one of the perfect poems. Gwendolyn Brooks won’t need much introduction to American readers, but I don’t think she is well known in England, or at least not as well known as she should be. I found about her in a workshop sometime after I moved to London.1

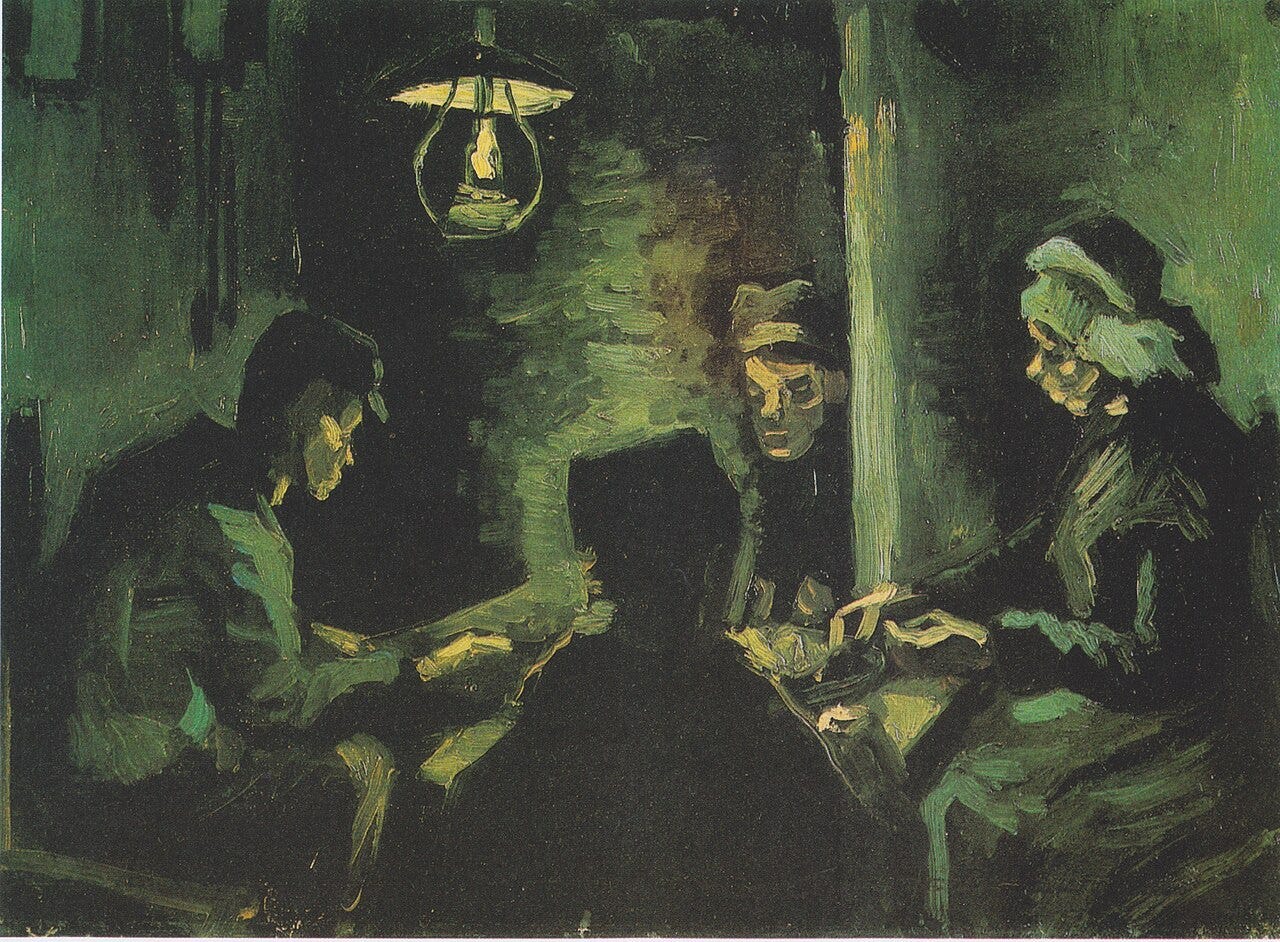

Then again, one of the things I love about ‘The Bean Eaters’ is that it needs so little introduction. It is a loving, knowing portrait of a couple who don’t have much. The title reminds me of Van Gogh’s ‘The Potato Eaters’. Here they are:

They eat beans mostly, this old yellow pair. Dinner is a casual affair. Plain chipware on a plain and creaking wood, Tin flatware.

Everything is reused, both words and their component parts: ‘plain’ is there twice in that third line, ‘chipware’ calls back to ‘flatware’. The original rhyme is everywhere, so much so that it becomes invisible. The poem is literally economical. It makes do. ‘Mostly’ returns again in the second stanza, where ‘putting’ is put to work twice and bodies become cupboards:

Two who are Mostly Good. Two who have lived their day, But keep on putting on their clothes And putting things away.

Already, I feel like there isn’t much else to say. Which is, like I say, no bad thing. Some poems speak for themselves. This is one of them. I think the last stanza speaks for itself, too, but writing about it made me like it even more.

And remembering ... Remembering, with twinklings and twinges, As they lean over the beans in their rented back room that is full of beads and receipts and dolls and cloths, tobacco crumbs, vases and fringes.

I love this. I love it because ‘twinklings and twinges’ seem so transparently engineered for the rhyme, for the links back to ‘remembering’ and forward to ‘fringes’ and furthermore because this doesn’t matter. Once in place, the words support each other. This is what remembering is. There is a quiet happiness in ‘twinklings’. There is something painful in ‘twinge’, but it’s a familiar pang. Some of their memories might be painful. Perhaps it is painful simply to remember.

I love this, too, because the form suddenly gives way to prose: the final two lines become pure list, as if all the objects in the room have forced themselves into the poem. The sudden rush is bitter-sweet: the poem knows that clutter is the opposite of plenty. Yet that clutter is also a sign of their shared life and of a different kind of wealth. Piles of memories, piles of stuff.

The list that arrives midway through Adlestrop launches us off into a waking dream. In ‘The Bean Eaters’ we’re left suspended on that last word, ‘fringes’: by the awkward, unresolved rhythm; by the image of old threads repeating endlessly; and by that rhyme which sends us right back to their memories, rattling between twinklings and twinges, memories repeating like fringes…

A note on list poems

Any list of ‘list poems’ is potentially endless. Here are a few I like: Christopher Smart’s My cat, Jeoffry, John Clare’s Emmonsail’s Heath in Winter, William Blake’s Auguries of Innocence. Auden’s Spain, which he later disowned, but which is in many ways the quintessential Auden poem, for better and for worse (I can imagine hating it). Auden is a list-maker.

Yesterday the assessment of insurance by cards,

The divination of water; yesterday the invention

Of cartwheels and clocks, the taming of

Horses. Yesterday the bustling world of the navigators.

Last time a reader remembered their professor saying that ‘all great poems are really lists’. Which, as they said, isn’t strictly true but is deeply suggestive.2 It takes me back to Auden, who used to argue that all poetry was a form of praise, and back to Edward Thomas, who made endless lists of proper names in his prose before he ever wrote a poem—not just flowers but the names of pubs and villages, houses and gravestones. Back to John Clare, too, whose poems often start with some variation on the line ‘I love to see’. Then he tells you what he loves to see. It makes me think of our toddler, whose favourite word at the moment is ‘more’.

All of which said, there is a recent vogue for poems which are purely, and only, lists which I am wary of and would like to gently warn against.3 It goes back to that question of what a poem ‘really’ is. This question tends to tie us all up in knots, but I trust the simple answer: the fundamental unit in a poem is the line (or phrase, since not every poem is written down). The way the lines move down the page, or the phrases move through time, is the poem and this is true whether or not you are writing in metre. This is form. Form wrests the poem away from the poet and opens up the possibility of surprise.4

A list is made up of things, not phrases. It is a bag into which you can drop any number of images and ideas in any combination, which means the list-maker is always in control. It is a long way from Robert Frost’s ice-cube on the hot stove, riding ‘on its own melting’. Perhaps every good poem starts as a list. But at some point, the poet has to let the poem take over. Which means letting go.

Thank you, Edward Doegar.

Thank you, Jeff.

Encouraged, I suspect, as a writing exercise. Of the poems mentioned earlier only the Christopher Smart is pure list.

I like prose poems and don’t mean to do them down by excluding them. If you are going to argue about this in the comments, please play nicely…

A beautiful poem